|

“The Rituals of Dinner” is a compendium of information about the world at table, from the Sherpas who send a child to summon guests to a dinner party (thus reducing the number of rejections, since the child knows neither the exact time nor the reason for the party, and is too young to be trusted with a reluctant guest’s contrived excuse) to the London hostess of the 1920s who sent handwritten invitations, again and again, until an elusive invitee, exhausted, gave in.

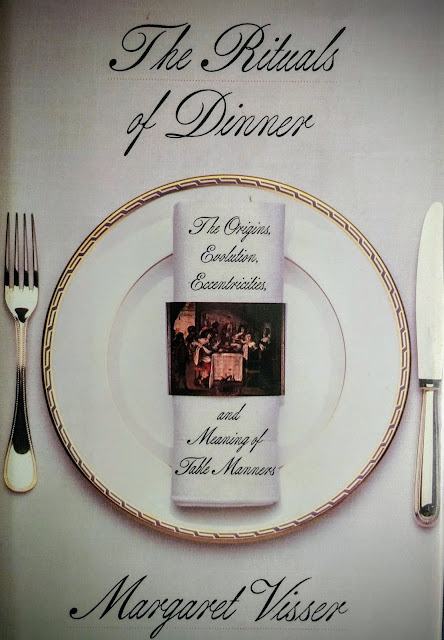

— Photo, Etiquipedia’s private library

|

Review of “The Rituals of Dinner: The Origins, Evolution, Eccentricities and Meaning of Table Manners,” By Margaret Visser

|

Author Margaret Visser writes on the history, anthropology, and mythology of everyday life. Born in 1940 in South Africa, she attended school in Zambia Zimbabwe, in France at the Sorbonne and the University of Toronto Canada where she earned a PhD in Classics. She now spends her time at homes in Toronto, Paris, and South West France.

— Photo, Etiquipedia’s private library |

The memory is about five years old, but vivid: A woman takes a table for one at a trendy Italian restaurant, orders a Caesar salad, and proceeds to eat it with her fingers. She picks up one long leaf of silvery green Romaine after another, always grasping the stem end, and then chews her way from the top of the leaf to her fingers.

The only thing more remarkable than her choice of utensils was the other diners’ reaction to it. All of us watched her. It was impossible not to. In a room full of people who were eating in the accepted manner, with a lot of gnashing flatware, this woman was breaking the unspoken rules. We were titillated and appalled. Who was this stranger, and how had she gotten in?

Food rules are a reassuring discipline, a way to prove who we are or to demonstrate who we’d like to be, a societal shorthand that betrays broad cultural attitudes. You are not only what you eat, but when, where, why, how and with whom. Margaret Visser may be a professor of classical literature at the University of Toronto by trade, but she is at heart a journalist, determined to answer the five W’s and an H that are the bedrock of that profession. To her credit, and to the reader’s unending, startled delight, she has succeeded.

“The Rituals of Dinner” is a compendium of information about the world at table, from the Sherpas who send a child to summon guests to a dinner party (thus reducing the number of rejections, since the child knows neither the exact time nor the reason for the party, and is too young to be trusted with a reluctant guest’s contrived excuse) to the London hostess of the 1920s who sent handwritten invitations, again and again, until an elusive invitee, exhausted, gave in.

Visser is a partisan of ritual, an admirer of structure at a time when newspaper stories herald the end of the family meal, and the at-home dinner party seems likely to become a museum diorama. She is aware that manners can be constraining, as in the story of the 15-year-old boy who humiliated his father by eating spaghetti with his hands at a business dinner, and was packed off to boarding school as a result.

She knows etiquette can be foolish, as she shows in a wickedly insightful section called “Learning to Behave,” in which she examines how we cope with our children’s heinous crime of not being miniature adults. But she acknowledges the more important freeing aspects of ritual, of feasts that are “celebrations of relationship among the diners, and . . . expressions of order, knowledge, competence, sympathy and consensus at least about important aspects of the value system that supports the group.”

Manners have belonged to the masses of the Western World since 1530, when Erasmus published de civilitate morum puerilium (On the Civility of the Behavior of Boys), which offered instruction on everything from table manners to behavior in the bedroom; before that, manners were the province of the social elite.

We have managed, in the intervening centuries, to act as though we made up the eternal rules of this game, and one of the best things about Visser’s book is the way she deftly skewers Western pretentiousness. She need only explain the genealogy of the chopstick--called kuai-tzu (fast fellows) by Chinese boatmen, and hashi (bridge) by the Japanese, since they close the small gap between the lifted bowl and the mouth--to make the reader realize the idiocy of trying to transport rice from a flat plate, at table level, as we do.

She is as sharp as the knives that symbolize, to her, the violence that lurks just beneath the service of every meal, and requires the imposition of manners to keep one of us from slicing up the lout who refused to pass the potatoes.

The wry tone of “The Rituals of Dining” is reminiscent of the scene in the Japanese film “Tampopo” in which a group of proper young women are being taught to eat pasta properly. Their instinct is to lift the dish and slurp appreciatively, but their teacher cautions them to swirl with a fork, lift, and chew silently, a discipline that dissolves quickly because it makes no sense to them. The same foodstuff but different cultures— and Visser has seemingly endless permutations with which to enlighten the reader. A dining room chair (or a stool, or a dirt floor, or whatever the seat of choice happens to be) is a wonderful vehicle for a trip around the world, and through time.

Is there anything missing? It seems a quibbling question. Visser’s range of knowledge is so broad that it’s impossible to know what to ask for: Since I never knew it was acceptable behavior to place bitten pieces of meat back in the boiling pot for warmth at an Inuit feast, I could hardly have faulted Visser had she omitted that morsel of information. There may be a detail out there that escaped her, but I defy anyone to name it. Having been served a sumptuous meal, the sated reader would be perverse to inquire if there was anything left in the literary kitchen.

The only thing that Visser does leave to the reader’s imagination is the deep emotional component of some of the rituals she describes. Yes, a seating arrangement might have everything to do with power, but some food rituals spring from a more intimate source, from the link between food and the life we share with the people who eat at our tables. Take, for example, the use of candles. “Candles last their predestined, visible length,” writes Visser. “They represent spans of time for us: a lifetime, with the flame as life itself, fragile but still alight (they become, with this meaning, potent symbols during political demonstrations); or a significant period of time, as when candles on a birthday cake mean ‘years lived.’ ”

That brief, lyrical passage, with its imitations of mortality, of the delicate ways in which we both celebrate and deny our temporary status, was almost shocking to read, sandwiched in between so many other bits of information. Perhaps the best way to approach “The Rituals of Dinner” is as thought were a meal shared with a remarkable friend— slowly, reflectively, savoring every exchange, not just for what it says but also for what it implies. — By Karen Stabiner, 1991

Etiquette Enthusiast, Maura J Graber, is the Site Editor for the Etiquipedia© Etiquette Encyclopedia